If I had to pick my all time favourite night time scene, it would be “View Of Dresden By Moonlight” painted by Johan Christian Dahl in 1839. The towers reaching majestically towards the heavens, the flares on the riverbank, the candlelit rooms in the distance and the sheen of moonlight on the water. (A very close second would be JMW Turner’s amazing watercolour “Alnwick Castle”, painted 10 years earlier.)

View of Dresden By Moonlight, 1839, 78 cm x 130 cm

You can see why he is considered the first great Norwegian romantic painter. In his series ‘Art Of Scandinavia’, art historian Andrew Graham Dixon paints a bleak picture of life in Norway in the years leading up to the arrival of Dahl on the artistic landscape. Norway was essentially a backward country of farmers and fisherman, cobblers and carpenters, there were no universities, art schools or art galleries so seeking an artistic career must have seemed a pipedream. Or an irrelevance.

But that didn’t deter Dahl who was the son of a poor west coast fisherman. His early paintings convinced a group of wealthy local merchants to sponsor his studies in Denmark and Germany, and he would spend most of his life abroad. Yet he would consistently return to his native Norway for inspiration.

Winter At The Sognefjord, 1827, 75 cm x 61 cm

Sometimes he depicted harsh winter scenes, in other paintings the sun would be shining, but it was always a pale watery sun struggling to break through the clouds. Graham-Dixon argues that Dahl saw the undeveloped landscape as a virtue, a symbol of Norway’s innocence.

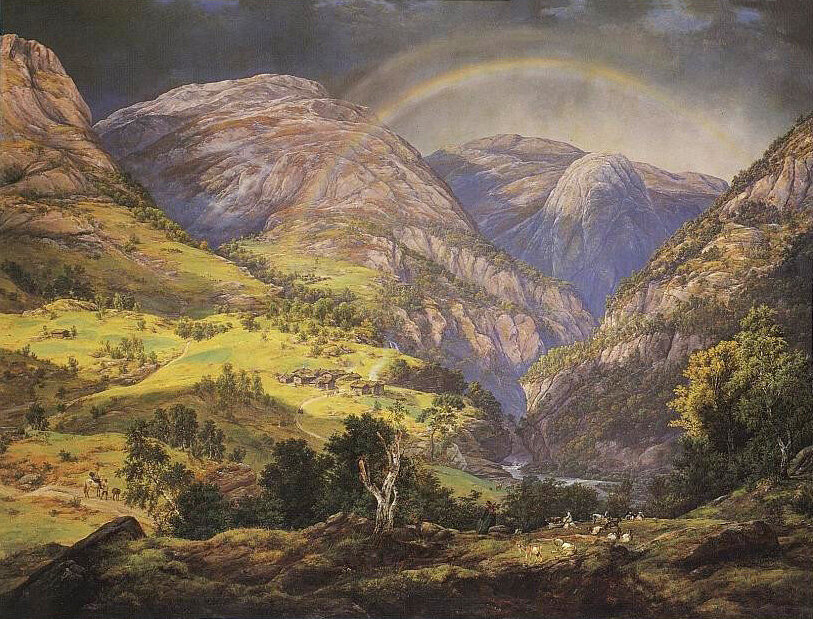

View from Stalheim, 1842, 190 cm x 246 cm

In his monumental “View From Stalheim”, Dahl seems to pull out all stops to produce a grand patriotic statement, perhaps presenting the essence of what it meant to be Norwegian at a time of rampant industrialization in other parts of Europe.

Dahl spent a large part of his life in Germany, settling in Dresden around 1820. He befriended the famous German romantic painter Caspar David Friedrich and they became very close and were godfathers to each other’s children. They painted and exhibited together and from 1824, even shared the same house with their respective families.

View From Lyshornet, 1836, 41 cm x 51 cm

The German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer asked in 1840 “Why has looking at the moon become so beneficiary, so soothing and so sublime? Because the moon remains purely an object for contemplation, not of the will. […] Furthermore, the moon is sublime, and moves us sublimely because it stays aloof from all our earthly activities, it sees all, yet takes no part in it…”

There is serenity and peace in Dahl’s painting of moonlit Dresden, a suggestion of nature and people coexisting harmoniously. We see the Augustus Bridge spanning the Elbe River and the Baroque Church of Our Lady in the middle distance, and to the right the Old Town (Altstadt) – the historic town centre. What could have been a meditation on loneliness and alienation has perhaps become a comforting scene, a reassurance that we are not alone.

References;

Art Of Scandinavia, presented by Andrew Graham-Dixon BBC 4 (2016)

artschaft.com – Johan Christian Dahl (2018)